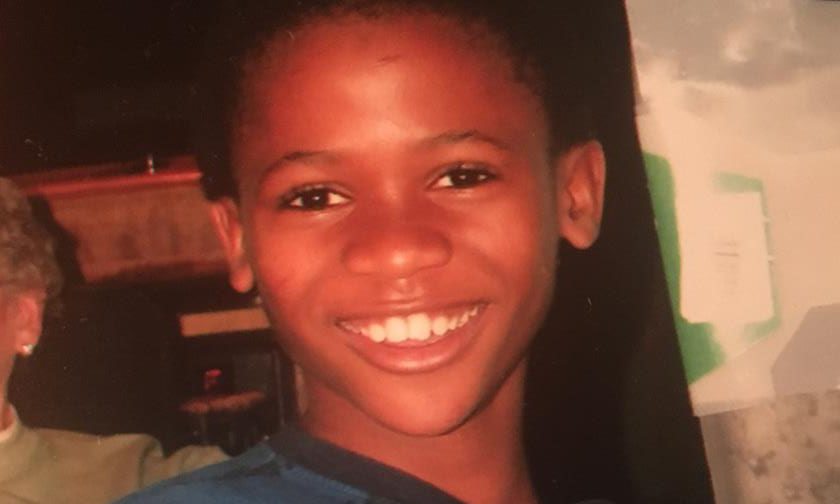

When Moses Bryant was a freshman, a rumor that he was actually 19 years old circulated at Elkhorn South High School. It started much earlier — when Bryant was a sixth-grader. The reasons behind that rumor, more so why it was perceived as credible, have roots in the West African nation of Sierra Leone.

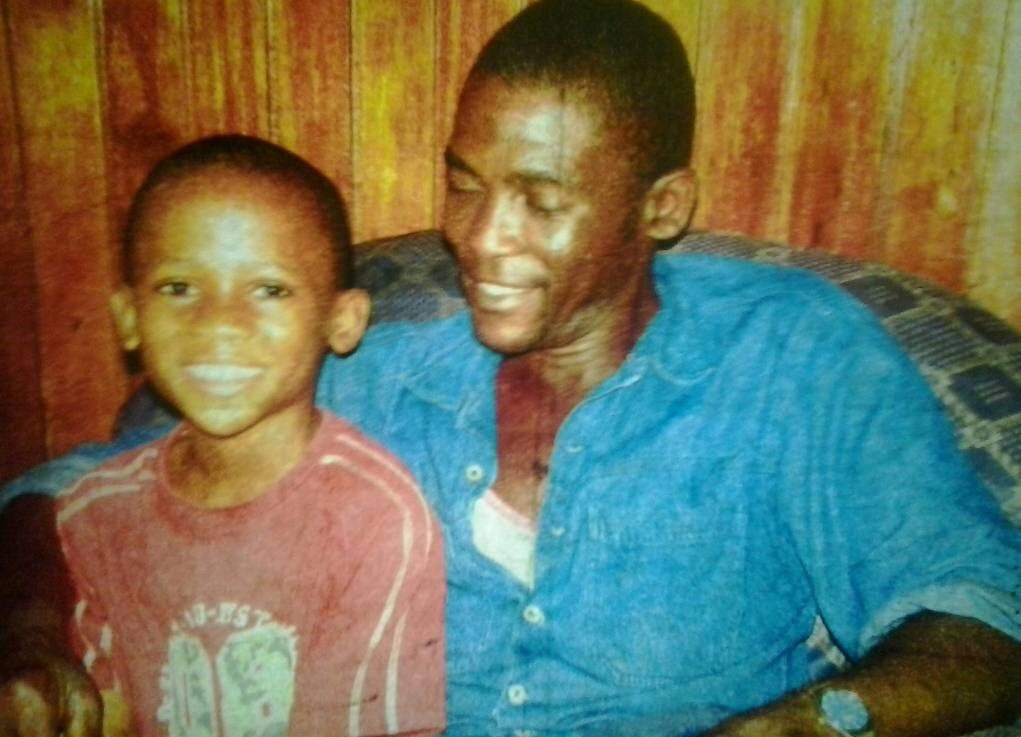

Bryant’s country of birth was embroiled in a bloody, brutal civil war from 1991 until 2002. More than 50,000 people died because of the violent conflict. When Bryant was just three years old, his father placed him in an orphanage, hoping to provide a better life. Bryant never saw him again.

Five years later, four of which entailed ongoing adoption proceedings, Bryant left the orphanage and Sierra Leone, setting out for America and the better life imagined by his father.

“The first thing I remember seeing was my new house,” Bryant said. “I thought it was the biggest house I’d ever seen. At first, I was somewhat scared to go inside.”

At eight years, old, Bryant didn’t know much about the United States, aside, he said, from Michael Jackson and David Beckham, one of whom isn’t American. His English was poor — most in Sierra Leone speak Krio, a language rooted in the Caribbean and influenced by the transatlantic slave trade.

“All I did was nod yes or no for everything,” Bryant said.

Eventually, Bryant caught on, thanks to the help of teachers, siblings, and general immersion. Though he began to understand the language, understanding the American school atmosphere took longer. It meant plenty of time in the principal’s office.

“Where I was from, we messed around. We joked around, “Bryant said. “I would always get in trouble for, like, throwing a ball at a kid or just playing around.”

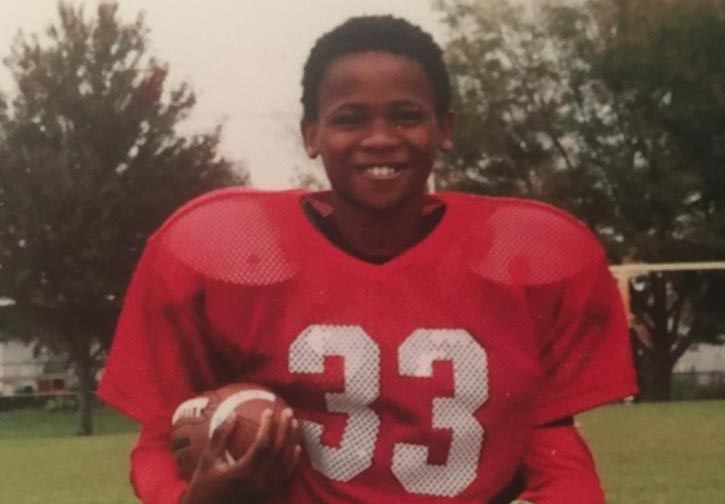

For young Bryant, playing around quickly became playing sports. Two friends, Nolan and Peyton Weiss, talked him into playing football. Soon, the kid from Sierra Leone, whose favorite athlete was David Beckham, gave up Association Football for the American variety.

Elkhorn South head coach Guy Rosenberg first saw Bryant play during a summer workout before Bryant’s freshman season. Rosenberg used Bryant as the rabbit in pursuit drills, but nobody could catch him.

In short order, Bryant moved up to work out with the varsity group. It took less than half of a summer workout.

Rosenberg recounts Tom Mueller, a coach on the freshman team, stopping the workout when Bryant was promoted. “There he goes, fellas. There goes your meal ticket. No more standing around waiting for Moses to make the play.”

Bryant never again played anything but varsity football.

Almost instantly, the Omaha metro knew the name Moses Bryant. His freshman season was outstanding, as Bryan went more than 150 yards rushing in each of the last six contests of 2014. He finished with 1186 yards and 17 touchdowns on the ground, averaging 9.1 yards per carry.

.@ESStormFootball‘s @mosesbbryant doing bad things……#nebpreps @ESStormCell pic.twitter.com/Y2JrmrIVHc

— World-Herald Photo (@OWHpictures) September 2, 2017

Attention came fast from far and wide. It was something Bryant was unsure of how to handle at first.

“I’ve always been a really quiet kid,” Bryant said. “I learned a lot from the coaches, too, on just how to handle myself when it comes my way.”

His coaches and parents urged him to remain humble and keep working hard. It’s something Rosenberg feels he’s most proud of Bryant for achieving.

“I’m a big believer that anybody can handle adversity. But if you really want to test someone’s character, let them have success, particularly at a young age,” Rosenberg said. “He does things the right way and is always looking to get better.”

“He does things the right way and is always looking to get better.”

As for that rumor, it’s unequivocally false. There would have been no way for Bryant to be adopted and moved into the United States if the paperwork, namely his birth certificate, wasn’t in order.

“In sixth grade, they were saying I was 18,” Bryant said. “Now they’re saying I’m 27, 28? Half those people just need to meet me and know who I am instead of just making up things.”

For Rosenberg, it’s even simpler. People aren’t used to seeing an athlete of Bryant’s caliber.

“That’s what a Division I football player looks like,” Rosenberg said. “They’re going to dominate.”

For Bryant, the domination of Class B football was only getting started.

As a sophomore, Bryant posted another 1181-yard rushing season with 17 rushing touchdowns, numbers nearly identical to his breakout freshman campaign. The Storm won the school’s first-ever state championship.

What followed the next season took Bryant’s legend into the record books.

As a junior, Bryant scored 43 total touchdowns to set a new Class B record. His 37 scores on the ground tied the mark set by Brendan Holbein in 1991. Holbein went on to play four years at Nebraska, winning two national championships.

Bryant’s 2016 yardage total, while not eye-popping at 1688, becomes incredible with context. Bryant carried the ball only 204 times, never carrying more than 23 times in a game. At 8.3 yards per carry, he was almost good for a first down every time he touched the ball.

Now in his senior season, Bryant has set the Class B record for career touchdowns. As of this posting, he’s crossed the goal line 94 times. It’s possible that Bryant could run down another Omaha legend: Calvin Strong. Strong scored 104 touchdowns in his career to set the all-class record. If Bryant maintains his career average of 2.35 touchdowns per game, he would have 101 touchdowns heading into the state playoffs.

Not bad for a 27-year-old.

Even better for a kid from an orphanage in Sierra Leone.