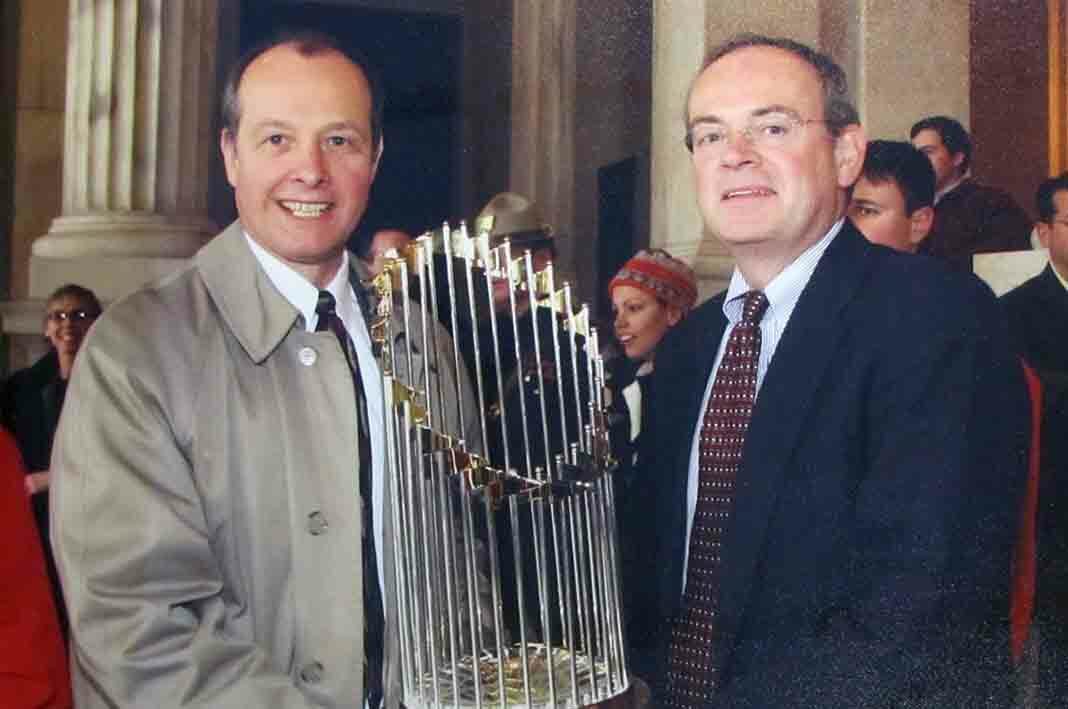

In PawSox circles, they were regarded as the Holy Trinity.

At the top was a businessman named Ben Mondor, a no-nonsense owner who breathed fresh life into the local Triple-A franchise after it had fallen into a state of disrepair.

You also had Mike Tamburro, Mondor’s top lieutenant who held the rank of club president and had a knack when it came to diplomacy.

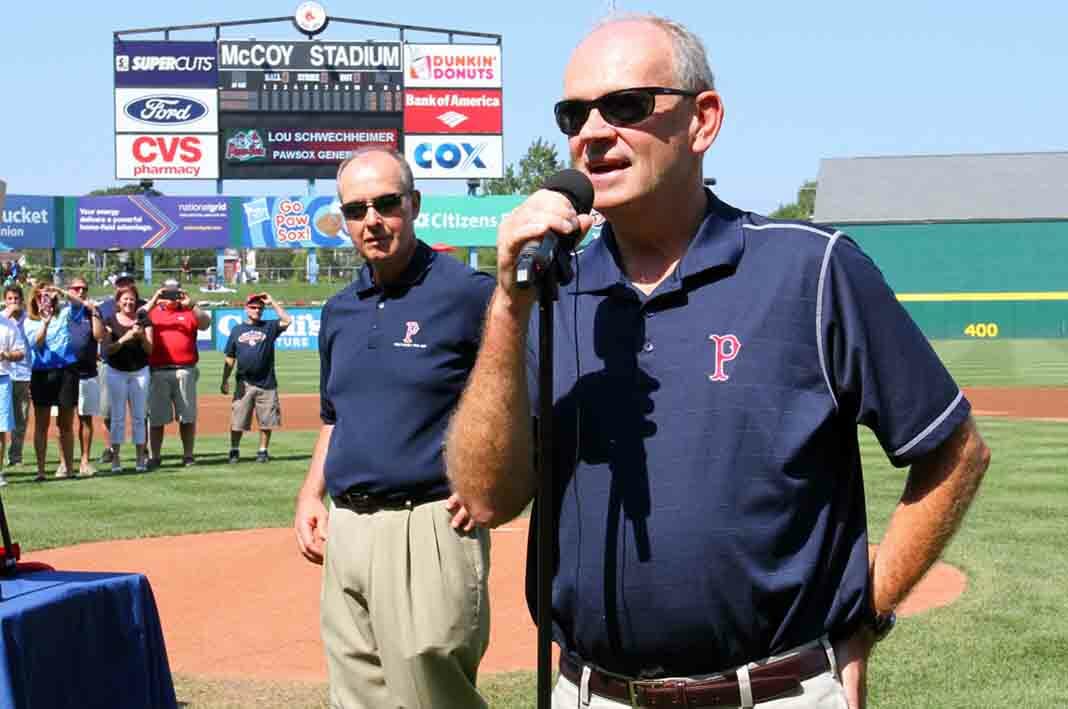

And then, there was Lou Schwechheimer, a seemingly endless fountain of hope who perfectly complemented Mondor and Tamburro as part of a three-person production that spanned decades and garnered industry-wide respect.

In Schwechheimer’s world, there was no such thing as a bad day – not when your office was located inside McCoy Stadium, which, for him, was the case for 37 memorable years.

“Lou would call me at 7 o’clock in the morning to tell me how beautiful the dew on the field looked,” said Tamburro. “He loved being around the ballpark. He loved being around the game.

“He always found the bright side. If a hurricane was coming, he would look for the one break in the weather so we could play,” Tamburro continued. “He was a special guy … the most optimistic guy you would ever want to meet.”

To Tamburro, there’s only one logical explanation as to why Schwechheimer left us last week at age 62 after a nearly three-week battle with COVID-19 – a virus that continues to take no prisoners.

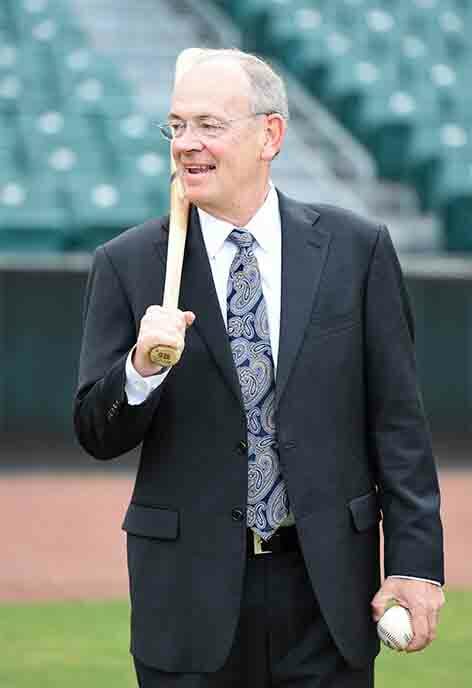

“Heaven’s baseball team must have needed a general manager. That’s the only reason why he’s gone,” said Tamburro, a nod to Schwechheimer’s PawSox front office role which he held starting in 1986 and did not relinquish until his departure from the club in 2015.

McCoy Stadium began serving as Schwechheimer’s longtime work address in 1979 when Mondor hired him as an unpaid intern. At the time, Schwechheimer was a 21-year-old undergraduate student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. A recommendation from longtime Red Sox publicist Dick Bresciani – Fenway Park’s press box was named in his honor after his 2014 death – to Tamburro helped Schwechheimer land on Pawtucket’s radar.

In no time, Schwechheimer earned his stripes as a tireless young addition to the management team already headed by two members of the about-to-be completed PawSox trinity. If the media game notes needed to be updated, Schwechheimer was on it. If the uniforms needed to be dropped off at the local laundromat, the odds are pretty good that Schwechheimer had already loaded them into his car and was on his way.

“He did such a good job that he ended up with a full-time job for the 1980 season,” said Tamburro.

At his very core, Ludwig Herman Schwechheimer Jr. was a people person.

He liked to share stories, none more prominent than the countless rounds of batting practice he threw to a future Hall of Fame third baseman named Wade Boggs. He loved to serve as an in-game tour guide for the PawSox Wall of Fame … stopping and explaining the significance behind a photo of Roger Clemens or the scorecard from the 33-inning ultra-marathon that in baseball lore is known as The Longest Game. Having a captive audience standing before him with all eyes looking in his direction meant the world to Schwechheimer.

“He had a warm personality … easy to meet and easy to talk to. Lou enjoyed the interaction,” said Tamburro.

From Tamburro’s point of view as the only staffer to work side-by-side with Schwechheimer during his entire Pawtucket tenure – Schwechheimer owned the kind of interpersonal skills perfectly fit for someone whose name appeared high up on the masthead. Together, this trinity of high-ranking PawSox leaders chartered a course which ultimately transformed a woebegone operation into one built on respect and reverence both locally and nationally.

“The PawSox would not have been what we became without Lou Schwechheimer. Ben and I get all the credit, but Lou deserves just as much credit as the two of us,” said Tamburro, who served as the best man at Schwechheimer’s wedding. “Each of us brought unique characteristics to our roles. We all meshed together very well and understood the fan was the important person who we would deal with.”

Schwechheimer was an idea man, a visionary who believed that all you truly needed was the right touch and a little elbow grease in order to make something work. When the PawSox hosted the Triple-A All-Star Game in 2004, Schwechheimer wanted to add a Celebrity Home Run Derby that, in turn, stretched the midseason extravaganza into a three-day fete. Tamburro recalls that it didn’t take long for imitation to become the sincerest form of flattery.

Tamburro noted, “He got the celebrities. The industry has been following his lead ever since. When it came to promotions, Lou had a great mind.”

As Schwechheimer rose to prominence, he never forgot how he got his foot in the PawSox door. When you consider him, the term “paying it forward” immediately springs to mind. Due to Schwechheimer’s molding, many impressionable individuals, who also happened to get their start as PawSox interns, went on to spread their wings in the sports industry.

“He ran the internship pool for a long time and took that seriously. He did his best to make champions out of those men,” said Tamburro.

And, while Schwechheimer may have retired from the PawSox, he wasn’t done chasing his baseball dream. He succeeded in carving out a prominent niche as the majority owner of two Minor League Baseball franchises under the Miami Marlins’ player development umbrella. The first was a Single-A team in Port Charlotte, Florida, while the other was a Triple-A operation that relocated from New Orleans to a brand-new stadium located in Wichita, Kansas. Nicknamed the Wind Surge, the Wichita ballclub was scheduled to open for business this season before the minor leagues became part of the coronavirus Great American Sports Blackout of 2020.

Last summer, Tamburro had the opportunity to check out the progress in Wichita.

“What Lou created after he left the PawSox was pretty special, too. I’ve got to tip my hat to him because he really went after his dream,” said Tamburro. “It’s heartbreaking that he never got to see [the Wichita ballpark] open.”

One of Schwechheimer’s key buzzwords was “magic:” continually finding himself in awe of the magic that occurred each time the ballpark’s lights were illuminated. For his entire adult life, this man who grew up north of Boston and was a diehard Boston Red Sox fan did something that he considered straight out of adolescent fiction.

“Lou was all about the magic,” said Tamburro.

Long may Schwechheimer’s magic continue to flow.